![]() By Dr. John R. Mishock, PT, DPT, DC

By Dr. John R. Mishock, PT, DPT, DC

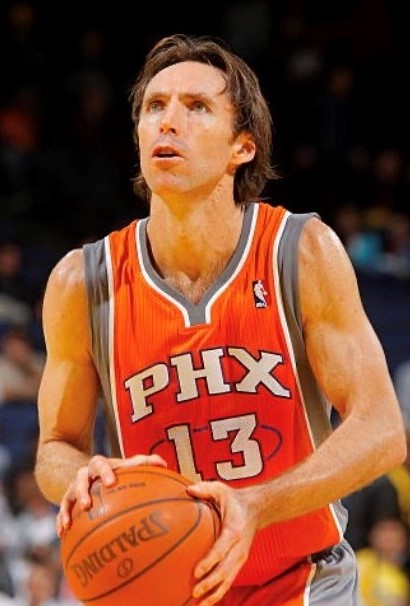

The elite NBA shooter can make 90% of free throws, 50% from the field, and 40% of their three-point shots. Nine players in NBA history have accomplished this sharp shooting feat of efficiency and consistency in a season. Steve Nash (Phoenix Suns) has done this four times, followed by Larry Bird (Boston Celtics) 2 times. (NBA, 2022) Even Stephen Curry (Golden State Warriors), known by many as the best shooter of all time, has completed the feat only once.

The ability to be a great shooter is multifaceted; however, it minimally takes countless hours (10,000 or more) of tedious, high-quality, perfect rehearsal to create great shooting mechanics. Possibly, the most underrated aspect of shooting mechanics is the eyes. Over the past 35 years, 26 high-quality research articles have explored the importance of the eyes in basketball shooting accuracy, specifically, the “quiet eye.”

The quiet eye is defined as the final focus point of the tracking eyes to a specific location or object (eye focus with a minimum of 100 milliseconds on a target). Simply put, it is the movement of the eyes to a given object (rim) and how long that focus point is maintained. Beyond basketball, over 100 studies show the importance of the quiet eye of elite performers in archery, billiards, golf, soccer, hockey, football, baseball, basketball, basketball, darts, and military shotgun activities. (Mann et al. 2007, Rienhoff et al. 2016, Vickers et al 2019)

Some basketball coaches and trainers intuitively tell their players to look at a spot near the rim (front center, eyelets, middle center, or back center) but spend most of their time working on the body shooting mechanics (feet, knees, trunk, elbow, hands) with little focus on the eyes. There is no question that shooting mechanics are essential to being a great shooter.

In this article, I will review the quiet eye research related to basketball shooting and how a coach can implement the quiet eye technique in shooting mechanics training, giving the player the best opportunity to become a great basketball shooter.

Why are our eyes critical in function?

By far, the most important organ of sense is our eyes. Up to 80% of the information from our surrounding environment reaches our brains through sight. The data from the site comes into our brain (visual cortex), where it is integrated and processed and then sent to the movement or motor center of the brain (parietal lobe, cerebellum, motor cortex) to make decisions on how to move. Even simple movement tasks such as standing and walking are difficult without the eyes. Try standing with your eyes closed or walking in the dark.

How are the eyes used during basketball shooting?

Before shooting a basketball, our eyes scan (saccades) and then focus on the rim, giving information on the best way to approach the basketball shot. That information is then sent to a specific part of the brain, which houses the memorized basketball shot (movement pattern engram) in preparation for movement.

How does our brain create great basketball shooting mechanics?

The memories of the basketball shot are created and stored in the brain (cerebellum, supplemental motor area, thalamus, vestibular system, and amygdala) as implicit or procedural memories, much like a recipe for the movement. In these procedural memories, the brain memorizes the; postural tone, equilibrium, balance, coordination, joint position, and muscle contraction type needed to repeat the basketball shot. With “perfect rehearsal” over time, movements become refined and developed through synaptic connections (nerve connections) and myelination (physiological nervous system refinement) of the nervous system.

This high-level process of neuroplasticity (brain learning) allows the player to automatically and efficiently perform at high rates of speed without conscious thought, aka “game speed.” It’s not about just putting up shots. The key here is a significant amount of near-perfect quality repetitions with great attention and focus on detail. Optimal neuroplasticity and adaptation also occur with frequent changes in the challenge of the basketball activity. For example, shooting practice with; a larger basketball ball, a rim shrinker, off the dribble, catch and shoot, with a defender, game speed, pressure, timed activities, etc.

How do the eyes and shooting mechanics work together?

During basketball shooting, the brain takes the practiced memory of the shot and combines it with information gained by the eyes. The combined stimuli are processed and incorporated into the preparation of the final movement. The perfect basketball shot combines the eyes (quiet eye) and the memorized movement patterns (engram), known as the visuomotor response. The visuomotor response takes approximately 200 milliseconds to perform. (Marques et al., 2018) This is why there are limits to shoot speed and accuracy.

How do elite basketball shooters use the quiet eye?

Technological advancements (mobile eye-tracking glasses) allow researchers to determine how elite basketball shooters use the quiet eye during basketball. Innately or through training, skilled basketball players demonstrate high-level use of the quiet eye by scanning for a specific spot near the rim and fixating on it while staying on that spot longer as they complete their shot. (Wilson et al, Vickers et al.)

In a study of free-throw shooting of professional players, the pro player spent 972 milliseconds focused on the rim, while near-experts spent 350 milliseconds. (Laby et al., 2019) The authors concluded that experts locate the target early, choose a single location, and maintain their gaze, and that the quiet eye prevents distracting visual information that could negatively impact their shot accuracy.

What part of the rim should the eyes focus on when using the quiet eye?

Studies have yet to determine the best part of the rim to focus on to gain the most shooting success. Stephen Curry (Golden State Warriors), one of the best shooters in the world, focuses on rim hooks (eyelets) that attach the net to the rim. His technique is to aim his eyes at the two or three rim hooks facing him and think about dropping the ball just over the front of the rim. (https://www.masterclass.com/articles/how-to-aim-your-shot-like-nba-pro-stephen-curry) Naismith Hall of Fame Coach Herb Magee, nicknamed “The shot Doctor,” recommends focusing on the back of the rim. (Herb McGee personal correspondence) Hall of Fame Coach Bob Koch, also believes that focusing on the back center of the rim leads to greater shooting success. (Bob Koch personal correspondence) Relative to the quiet eye, it may not matter where your eyes focus on the front, middle, or back of the rim. The key is for the player to lock in early to the spot without eye movements and stay there through the duration of the shot.

How does quiet eye training affect free-throw shooting?

Vickers and colleagues in a landmark study found that elite basketball players would fixate the eye on an area near the rim earlier and longer than novices. They found that training the quiet eye could significantly improve free-throw shooting by 23% as a team. The study included three groups of Canadian college basketball teams over two seasons. All three groups practiced free-throws after practice. Group A received quiet eye training during the shooting practice. Teams B and C did not receive quiet eye training while rehearsing. Following the training, the average player from group A improved their focus on the rim from 782 ms to 981 ms. Team A, who trained using the quiet eye, improved their free throw shooting from 54% to 77%, Team B declined from 68% to 66%, and Team C improved from 61% to 71%. In practice, Team A took fewer shots than Teams B and C. (Vickers et al. 2001) The 77% is 1.8% higher than the NBA and 2.8% higher than the WNBA team averages for free throw shooting. (NBA &WNBA, 2021)

How does the quiet eye affect the jump shot?

Jump shots have been studied from; a standing position, off the dribble, and after the pass. The latter two have been studied with and without a defensive player. The elite shooter’s eyes go to the rim for focus and stay there from the arm flexion phase to the end of the follow-through (wrist flexion and the fingers down) during the jump shot. Similar to free-throw, the jump shot shooting accuracy increases with more extended quiet eye period. The shorter the gaze fixation time, the poorer the shot accuracy. (Van Maarseveen et al, 2018)

How does a defender affect the jump shot?

Studies from Klostermann, Rojas, and Vickers found that while defended, the jump shooter will; release the ball quicker with greater arc, increase their jump height, and have a quiet eye gaze later during the shot. Individuals who trained using the quiet eye with an early focus on a specific point at the rim improved their shooting percentage while being defended. The early focus on the rim reduces the distraction from the defender.

How do exertion and fatigue affect the eyes?

A study looking at fatigue while basketball shooting (2-point jump shots and free throws) showed that fatigue and exertion cause the eyes to wander with more frequent fixation points. There is also reduced fixation time on the rim. The authors emphasized the importance of practicing shooting during fatigue with a particular focus on early quiet eye focus on the rim. (Zwierko et al. 2018) Fatigue would also cause the legs, hips, and core to fatigue, which would be an additional factor in poor shooting—another reason why it is crucial to train shooting during exertion and fatigue.

How does the eyes change with shooting 3-point shots?

Stexiuk and colleagues found that as the player moved back to the three-point line, shot accuracy decreased, and there was less fixation or focus on the rim. However, the shot accuracy increased for those who were shot-ready with an early quiet eye. The authors encouraged finding the quiet eye focus point at the rim before the catch when waiting to receive the ball. The players who were in a shot-ready body position shot with more accuracy. Like previous research, the longer the quiet eye duration, the better.

What happens to the eyes under threat, anxiety, and pressure?

When anxiety or threat exists, our brains move into a sympathetic response of “fight, flight, or freeze.” This sends the brain activity back to innate evolutionary behavior, causing the eyes to rapidly scan the environment creating many focus points. Rapid eye movements were an evolutionary advantage when locating or evading predators in the wild. However, this reduced quiet eye activity becomes a distinct disadvantage in sports, especially shooting a basketball.

How does threat, anxiety, and pressure effect basketball shooting?

Wilson and colleagues examined how anxiety and stress influence visual attention in free-throw shooting. They found that stress during shooting significantly decreased quiet eye fixation (886 milliseconds without anxiety, 330 milliseconds with anxiety) and led to increased misses as the pressure ramped up. (Wilson et al. 2009)

Giancalilli and colleagues studied free-throw shooting and the quiet eye in a threatened state (stress and pressure). They found that elite shooters had superior attention control compared with earlier and longer focus on their spot (front or back of rim) to semi-elites across all conditions. The authors concluded that the quiet eye could resist the adverse effects of anxiety and threat on free throw shooting.

The pressure and anxiety cause the individual to “think” vs. “do,” leading to rapid eye movements without fixation on one spot at the rim, making it difficult for the brain to figure out the final destination of the fine motor shooting task. So, the player with great mechanics may miss the shoot due to eyes and not the mechanics.

How does quiet eye training help to improve shooting performance under threat, anxiety, and pressure?

The quiet eye enhances “attention control.” Attention control inhibits all irrelevant information, allowing the athletes to focus on their task without being distracted by internal (negative self-talk or emotions) or external (nose of the parents, coaches, or crowd) distractions clearing the mind. With the quiet eye, the athlete is performing “in the moment” (mindfulness), focusing on the rim, letting his memorized basketball shot take hold, not the stimulus causing the distraction. Keep in mind, our higher-level brain (cerebral cortex) can only focus on one thought at a time. We cannot focus on the shooting, negative self-talk, coaches, and the noise of the crowd at the same time.

This enhanced attention control is the difference between the player being in the “zone” or “flow state” and “choking.” The zone or flow state (optimal mental state associated with peak performance) is the ability to have extreme focus during a task. (Marques et al. 2018)

Choking occurs when the player is distracted away from the task at hand. A threat, nervousness, and self-doubt can override the existing motor program of automaticity, causing degradation to potentially novice movement patterns. Choking happens when the athlete begins to “think” vs. “read-react.” The quiet eye allows the brain to revert back to automaticity of the memorized movement pattern optimizing the performance. Great performances happen when playing in the moment.

Can you improve performance with quiet eye training under anxiety and pressure?

Vine and colleagues found that quiet eye training leads to better visual attention control and a more extended quiet eye period (from 390 milliseconds to 505 milliseconds) under threat and pressure conditions resulting in better shooting performance.

Giancamilli and colleagues showed that the athletes who augmented their quiet eye in high-pressure conditions did not experience performance degradations in free-throw and three-point shooting, in contrast to those who did not adopt that strategy.

What is the best way to train three-point shooting using quiet eye research? (Vickers et al. 2001)

For the passer:

1. The pass is critical for success.

2. The pass should be made to the shooter’s hands or at a location that the shooter prefers.

3. For right-hand shooters, the pass should come from the left side of the court (facing hoop). This allows the pass to be caught on the shooting hand.

For the shooter:

1. Before receiving the pass, be in a proper body position to shoot (feet set, knees bent, trunk bent, and hands up and ready).

2. Attempt to visually locate the focus point on the hoop before receiving the pass.

3. As the pass is thrown, move your eyes to the ball as it leaves the passer’s hand and tracks it closely.

4. As early as possible, shift your gaze rapidly to the center of the hoop (front, middle, back) and no other location. This may be specific to the individual coaches’ experience.

5. Maintain a fixation on the center of the hoop and shoot.

6. Shoot using great mechanics as quickly and fluidly as possible.

7. Verbal cues: “Finish with hand in the basket” (external feedback). “Finish with the eyes.”

8. Focus on quality vs. quantity.

9. Consistently adapt and change the training to be game specific for better neuroplasticity and training.

For defending the three: When defending the three based on the quiet eye research, it should include

1. Disruptive defense (hand in the face) before and during the quiet eye catch.

2. Defensive pressure in the visual field of the shooter during the quiet eye arm flexion and arm extension.

What is the best way to train free throw shooting based on the quiet eye theory? (Vickers 2001)

Pre-shot routine:

This is a set of repetitive behaviors performed before the final execution of the shot designed to improve concentration and performance. (Amberry 1996)

1. Before receiving the ball, take controlled, slow deep, mind-clearing breaths behind the free-throw line.

2. Visualize the basketball “swishing” into the bottom of the net.

Free-throw routine:

1. Take your stance at the line with your head up and direct your eyes (quiet eye) to the hoop (center front

2. eyelet, center middle, or center back of the hoop), dependent on the coaching philosophy.

3. Bounce ball (1-3 times) repeat the phrase “nothing but net.”

4. Hold the ball in your shooting stand and maintain a quiet eye on a single location for approximately 1.5 seconds.

5. Keep the gaze stable on the one location accompanied by the words “sight, focus.”

6. Shoot using a quick, fluid action. “Swish”

7. Verbal cues from the coach: “Focus on the back-center eyelet of rim.”, “Sight, focus, swish”, “Hand in the basket,” “Finish with your eyes.”

The elite NBA shooter misses 6 of 10 three-point shots and 5 of 10 from the field. Great basketball shooting requires high-level shot mechanics, which takes thousands upon thousands of high-quality perfect repetitions at game-specific situations and speed. As demonstrated above, adding the eyes (quiet eye) can significantly improve ability in; free-throw shooting, jump shots, defended shooting, 3-point attempts, and shooting under threat and pressure.

If pain or limited function is keeping you from doing the activities you enjoy,

We can help!

Reduce pain and increase function

Schedule your visit 610-327-2600

https://mishockpt.com/request-appointment/

Gilbertsville – Skippack – Phoenixville – Boyertown – Pottstown – Limerick

Appointments available 7:00am to 8:00pm, ALL locations, most days!

Saturday Appointments available

Visit our website to REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT, read informative articles, meet our physical therapy staff, and learn about our treatment philosophy.

Email your questions to mishockpt@comcast.net

Dr. Mishock is one of only a few clinicians with doctorate level degrees in both physical therapy and chiropractic in the state of Pennsylvania.

He has authored two books; “Fundamental Training Principles: Essential Knowledge for Building the Elite Athlete”, and “The Rubber Arm; Using Science to Increase Pitch Control, Improve Velocity, and Prevent Elbow and Shoulder Injury” both can be bought on Amazon.